By Elliot Haspel, The Washington Post, March 25, 2019

“As a parent, I worry about many things. Some are concerns I imagine to be universal and shared by parents from time immemorial: Are the children healthy, are the children safe? Yet there’s also a suite of uniquely modern anxieties that can be summed up as “How is my kid stacking up?”: Should they know their letters by now? If she switches extracurricular activities too often, will it look bad on a college application? These stresses about our children’s development can be consuming, suffocating.

I’m here to give you permission to breathe.

I’ve spent my career working in K-12 and early-childhood education. There’s precious little that researchers agree on when it comes to what works best for children — witness the raging debates over school choice, funding, curriculum, and much more. Yet here’s a consensus for the wide-ranging topics of potential parental worries: Children who have loving, predictable, secure relationships with adults are set up to thrive. Positive relationships are the undisputed, undefeated, take-down-all-comers champion of child development.

Don’t take my word for it. Here’s an interdisciplinary set of experts in the report “From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development”: “Children grow and thrive in the context of close and dependable relationships that provide love and nurturance, security, responsive interaction, and encouragement for exploration … children’s early development depends on the health and well-being of their parents.”

That sleep loss we suffer over, from academic success to kindness, can be quelled from just loving the heck out of our kids. This doesn’t mean being perfect and never slipping up or raising our voices; kids’ brains respond to the aggregate sum of their relational experiences. They need those boundaries, and it’s okay if we parents aren’t perfect.

Journalist and author Paul Tough writes in the book “How Children Succeed” about a powerful Minnesota study that showed: “In preschool, two-thirds of children [who had been securely attached to caregivers at infancy] were categorized by their teachers as ‘effective’ in terms of their behavior, meaning they were attentive and engaged and rarely acted out in class. … The researchers followed the children through high school, where they found that early parental care predicted which students would graduate even more reliably than IQ or achievement-test scores.”

Perhaps most poignantly, here’s Bruce Perry, the child psychologist and trauma specialist who has worked with children from the most horrific of circumstances, such as the survivors of the Branch Davidian cult in Waco, Tex.: “Relationships are the agents of change, and the most powerful therapy is human love.”

Yet this decidedly is not the message that modern parents receive.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Time spent with children today isn’t much different, in number of hours, than it was in the past. But time spent on hands-on activities together has increased the most. So although they spend time with their kids, parents feel more stressedand rushed and as if they aren’t actually there with their children.

I have a proposal, parents: Let’s redefine what it means to be a good parent.

Certainly each child has different needs, and hands-on care isn’t inherently bad. But universally, children need the same foundation, and this is where the focus should be.

Let your children know that they are loved and that nothing they can do will ever make you love them any less.

Respond to your children’s bids for attention. That doesn’t mean you always have to do what they want, but look them in the eye and make sure their need is addressed, even — or especially — if that means coaching them to address it themselves.

Be predictable. Children need to know that when they cry, they will be comforted. They need to know that when they have a question, their voice will be heard (though they may have to wait until it’s appropriate). When you’re unpredictable, talk about it afterward and make up.

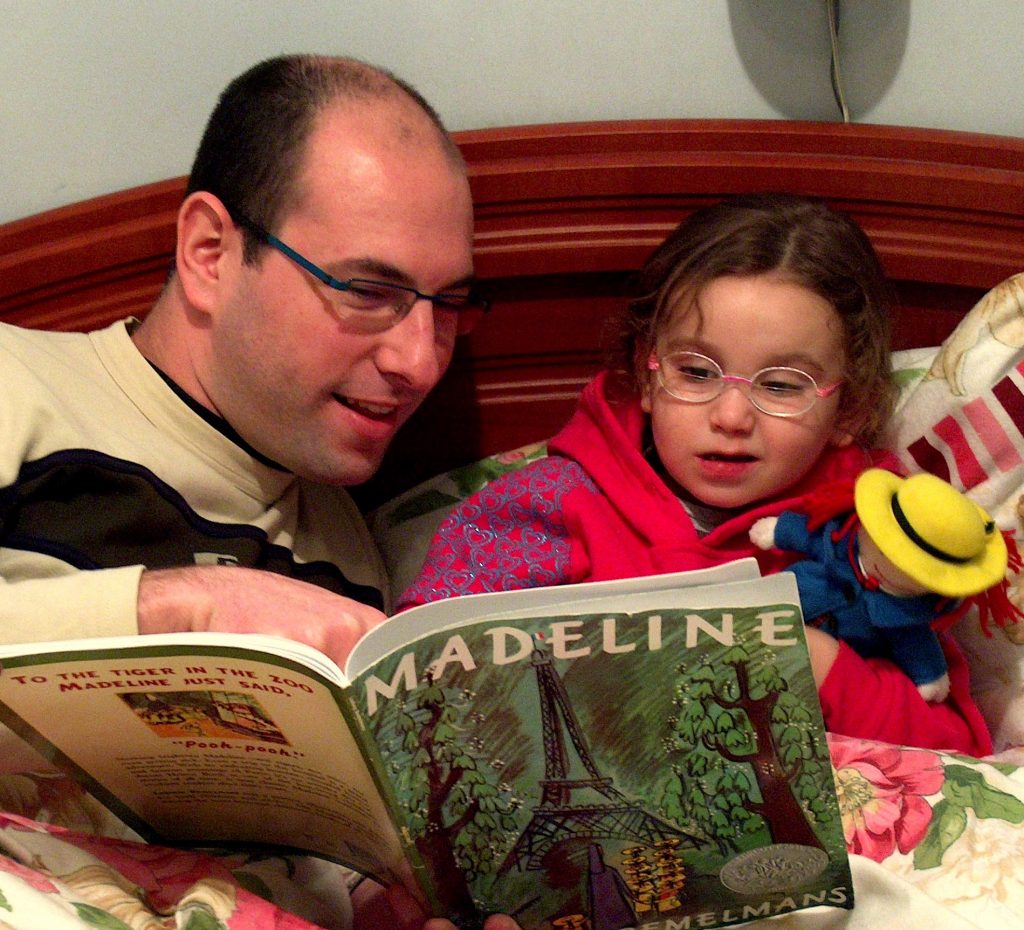

Find time for intentional interactions. Read a book to them. Go for a walk together. Bake cookies. It doesn’t have to be long — children have an entertainingly terrible sense of time — just make it a consistent routine. Intentional time, even 15 minutes, is relational gold.

If all you ever do for your child is provide basic physical needs and cultivate a warm, predictable relationship (and, okay, read with them a lot), they will be in amazing, fantastic shape for life. The best part is that in cultivating that relationship, you’re naturally going to cross into spheres of literacy and numeracy and physicality and character building and supporting their passions and all the other million developmental things we stress about daily.

More than anything, this means parents can give themselves permission to take a deep breath and relax their shoulders. If the shoulders won’t budge, think about it this way — reducing stress improves the ability to build relationships, so slowing down on trying to help your kid succeed is actually helping your kid succeed.

Despite recent headlines and fallout from them, society will frown upon (at least for now) those who opt out of the overscheduled, pressure-filled model of parenting, despite its disconnect from the way young brains develop. Be strong, parents. The best thing we can do for ourselves and our children is to adopt the new mantra: Relationships first.”

Elliot Haspel is a former elementary school teacher who works in early childhood and K-12 education policy. He holds an M.Ed. in education policy and management from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. He lives in Richmond with his wife and two daughters.

Great post! This was just the kind of advice I needed as a young parent. A friend, who happened to be a child psychologist, once told me, “If a child never falls, he will never learn to pick himself up.” That helped my shoulders relax!